A Journey to the World Nomad Games: Tradition, Culture, and Modern Kazakhstan

“Blending” into yurt traditions at the 2024 World Nomad Games, Kazakhstan (image: Stephen M. Bland)

In July 2024, my friend and former musician-turned-journalist Stephen M. Bland reached out with an unusual proposal: would I like to join him in Kazakhstan to cover the World Nomad Games (WNG)? Originally from London, Stephen's fascination with Central Asia began in 2012 during a spontaneous trip to the region, which inspired his travel memoir, Does it Yurt? Travels in Central Asia or How I Came to Love the Stans. That book paved the way for him to become a journalist and occasional BBC correspondent covering Central Asia and oligarchies, and later, the editor of The Times of Central Asia (TCA), one of the region's largest online news outlets.

TCA was an official sponsor of the 2024 WNG, held in Astana, Kazakhstan, from September 8 to 13. With Stephen’s encouragement, I authored an introductory piece about the games for TCA, which approved my trip to Central Asia and commissioned several articles on the event.

The 2024 WNG brought together approximately 3,000 athletes from 89 countries, including American Cowboys, to compete in events rooted in nomadic traditions. While relatively new—first held in Cholpon-Ata, Kyrgyzstan, in 2012—the games revive centuries-old nomadic practices that have been shaped by the rugged Eurasian Steppe. Subsequent editions were hosted in Cholpon-Ata (2016, 2018) and İznik, Turkey (2022), before Kazakhstan was selected for the fifth installment.

The WNG celebrates sport, science, culture, and the nomadic ethos of resilience. The athletic contests, from horseback archery to kokpar—a dramatic game involving a goat carcass—mirror the ancient resourcefulness and physicality essential to survival on the steppe.

Uzbekistan Airways inflight “entertainment”

I chose the budget-friendly route, flying with Uzbekistan Airways from New York’s JFK Airport to Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, before continuing to Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan. The in-flight entertainment primarily consisted of Russian films, whose English translations I found noteworthy enough to document. Among the titles were Love Doesn’t Love, Happy New Year, Mommies!, I Am Losing Weight and A Couple from Future. While Russia has historically produced some of the world’s greatest cinema, none of those masterpieces made the list. To make matters worse, the Uzbekistan Airways headphones delivered the Russian dialogue to one ear, while the other ear received a monotonous, broken English dub seemingly voiced by the same Russian man for all male characters, in the vein of: “I love you, why don’t you love me? Let us love one another and stop waste time.”

Waiting for a connecting flight to Astana at Islam Karimov Tashkent International Airport in Uzbekistan provided me with an impromptu sketching subject: a man who stared at me for 4 hours.

The final leg—a two-hour flight to Astana—ended with a taxi ride past banners promoting the WNG.

I reunited with my friend Stephen—who’d journeyed from his home in Spain—at our Airbnb, both of us jet-lagged but eager to find a local bar.

Despite Kazakhstan being a predominantly Muslim country, the Respublika Pub—enticing customers with “beer and beef”—and the Kings Cross Pub—with Harry Potter-themed embellishments—were among the many establishments frequented by both men and women.

Experiencing Astana’s nightlife with TCA staff and local residents

Spanning Central Asia and a small part of Eastern Europe, Kazakhstan is the world's largest landlocked country and the ninth-largest overall. Despite its vastness, it has a modest population of just under 20 million. Rich in natural resources, including oil and gas, Kazakhstan boasts the most developed economy in the region.

Until 1997, Almaty served as Kazakhstan’s capital—a larger, more culturally vibrant city with a history dating back over three millennia to approximately 1000 BCE. However, the government relocated the capital to the northern city of Astana, a name that literally means “capital city.” Astana was conceived as a futuristic showpiece, embodying the ambitions and vision of Kazakhstan’s long-time leader, Nursultan Nazarbayev. Rising from humble beginnings as a steelworker, Nazarbayev became one of the most influential figures in Kazakhstan’s history. He rose through the ranks of the Communist Party to serve as the nation’s final Soviet-era leader, later becoming its first president in the post-Soviet era and the personification of its carefully cultivated identity. Although he stepped down in 2019, his legacy remains deeply intertwined with the complex and often painful history of Soviet rule, which left lasting scars on Kazakhstan.

Astana is a stark symbol of political controversies, including corruption and inequality, that have shaped the country’s history.

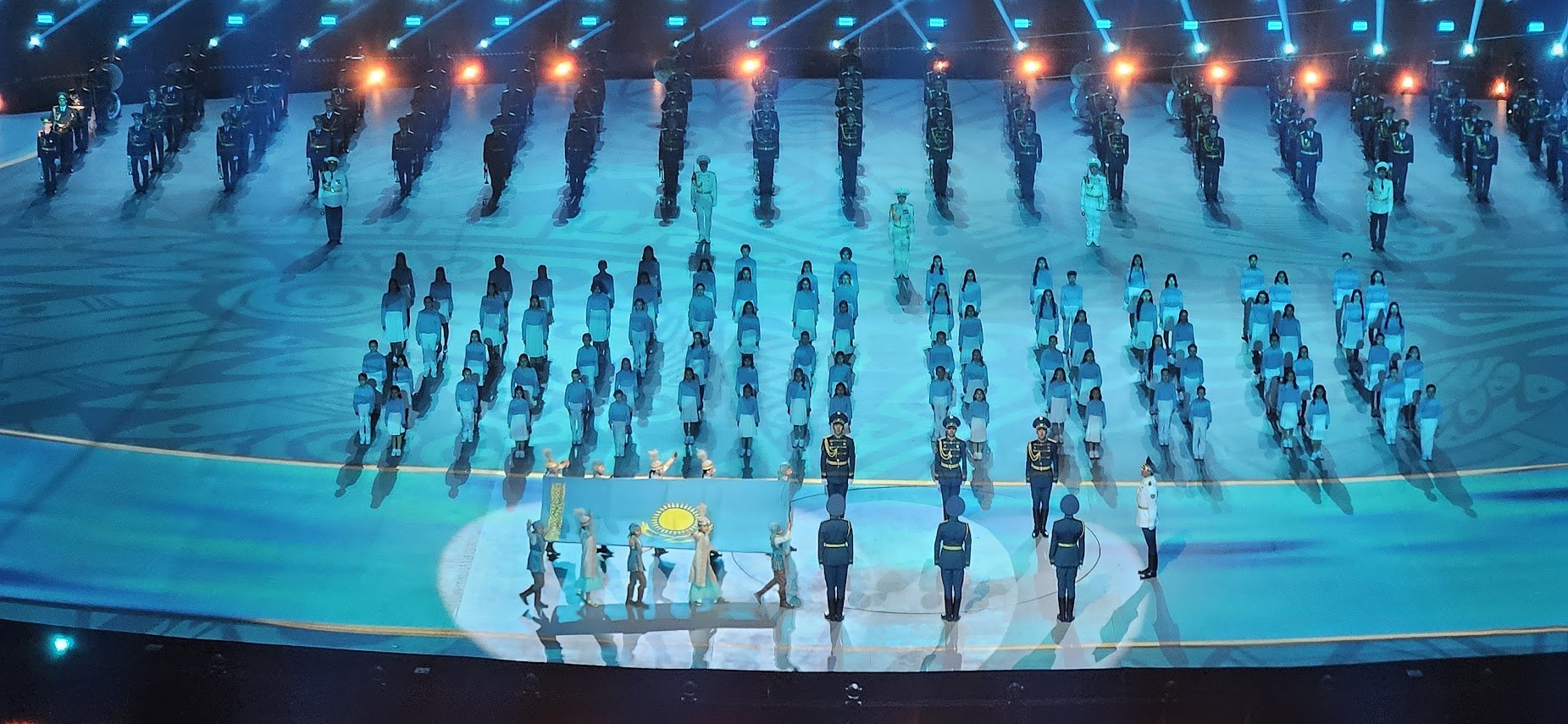

2024 WNG Opening Ceremony

The day after my arrival marked the opening ceremony of the World Nomad Games, themed “Gathering of the Great Steppe.” After a prolonged dispute over a supposed press ban, during which Stephen reminded officials that TCA was an official sponsor, we finally gained entry to the Astana Arena, the country’s largest stadium. The ceremony showcased a vibrant blend of pomp, tradition, musical performances, and military flourishes.

Team America

Athletes from 89 nations paraded across the vast stage as a traditionally-clad Kazakh woman on a white horse performed continuous laps around its circumference. The U.S., represented by American Cowboys, received a warm welcome from the crowd.

Team Kazakhstan

As expected, the loudest cheer was reserved for Kazakhstan, hosting the World Nomad Games for the first time.

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev

Central Asian leaders, including Kazakhstan’s President Tokayev, attended alongside representatives from UNESCO and the European Union. Tokayev spoke of reviving the nomadic spirit in a globalized world, a theme echoed throughout the event.

Over the next few days, as the designated roving reporter, I wandered through various WNG venues with minimal information, unclear game rules, and little available translation, searching for something… anything… to write about.

Among the sporting highlights were the kokpar and kok boru matches at the Kazanat Hippodrome. Often described as a rugged mix of polo, hockey, and football on horseback, these games involve teams vying to deposit a goat carcass (swapped out for a pig-skin dummy at the WNG) into the opposing team's goal. The Kazakh team dominated the Americans 18-0, much to the delight of the spectators.

East Versus West: Kazakhstan vs. United States in a game of Kok Boru

Meeting the spectators of Kok Boru

Women also shone at the 2024 WNG, garnering significant support in events like wrestling, archery, and horseback competitions. Their participation hinted at the evolving inclusivity of these traditionally male-dominated sports.

Traditional Archery

Ethnoaul (Ethnic Village)

The WNG’s Ethnoaul (Ethnic Village) offered visitors a glimpse into traditional nomadic Kazakh life.

Amid the roaming beasts and flapping birds of the Ethnoaul, the Kazakh Tazy—a 4,000-year-old hunting dog breed—captured much attention. Dogs, horses, and birds of prey have long been indispensable allies on the Great Steppe, a role they continue to play in the World Nomad Games.

One yurt hosted reenactments of nomadic marriage proposal traditions between two uniting families, complete with dombra music, symbolic gifts, and familial rituals. Actors, like Ernur from the Mukanov Theater, brought these traditions to life, blending formality with immersive storytelling.

In reality, and due to enforced restrictions on herding routes under the Russian Empire, and sedentarization inflicted by the Soviet Union, little of the nomadic culture still exists in Kazakhstan. Reviving these traditions, in tandem with hosting the 2024 WNG, is an attempt to restore a sense of national identity.

Beyond the WNG, Astana—a symbol of post-Soviet ambition—demanded exploration. While the capital is clean, safe, and visually appealing, its relatively recent creation and authoritarian origins leave it with a noticeable lack of character. However, Astana stands out aesthetically with its numerous bars, sprawling gleaming shopping malls, ornate decorations, and futuristic architecture.

MEGA Silk Way (shopping mall)

Mangilik El Triumphal Arch

The name of the arch means “Eternal Country,” representing post-Soviet independence.

Inside the Military Historical Museum

Inside the Future Energy Museum

The city’s most iconic observation tower, the 105-meter-tall Baiterek, was built to commemorate the transfer of Kazakhstan’s capital from Almaty to Astana in 1997. The monument represents a folktale about the mythical Tree of Life, where a magic bird of happiness laid its egg in the crevice between two branches.

Baiterek Monument

The significance of the Baiterek ("Tree of Life") as a symbol of a new stage in the life of the Kazakh people is stamped, quite literally, with the hand of the “Great Dictator”—former President Nursultan Nazarbayev—at the top of the tower.

Visitors are encouraged to place their hand inside an imprint of Nazarbayev’s hand, an act that I reluctantly complied with despite the absence of peer pressure.

High dreams conduct to tops

Kazakhstan’s complex history was evident at Astana’s National Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan, where a room dedicated to Nazarbayev reflected the lingering influence of the nation’s first president, despite removing his statue in 2022 following civil unrest. The museum’s translations of his “sporting wisdom” provided unintended amusement.

A work in progress: Astana Light Metro

Regarding architecture and infrastructure, Astana lacks local rail transportation. Although groundwork for the Astana Light Metro began in 2011, it remains an unfinished overhead railway line, intended to span the city and include an airport connection. Large, segmented gaps in the concrete reflect years of disorganized construction. The project’s completion has been repeatedly delayed, hindered by bankruptcy and rumors of embezzlement, elements that fit into Nazarbayev’s legacy. Construction resumed in 2023, with the Metro now scheduled to officially open in 2025. However, the Astana residents I spoke with remain far from optimistic.

Kosmonavtlar Tashkent Metro, Uzbekistan

On my return journey to New York, during an extended layover in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, I visited the Kosmonavtlar Metro Station, designed as a tribute to Soviet cosmonauts. Until 2018, the station also served as a designated nuclear bomb shelter. This visit was a striking reminder of the region’s historical ties to the Russian Space Program and provided a fitting conclusion to a journey that explored the intersection of Central Asia’s past and present.

Words and images by K. Krombie